Swinburne Hale

(b. Ithaca , New York ,

5 April 1884; d. Westport , Connecticut

Swinburne Hale was the oldest of four children of William

Gardner Hale (1849-1928), Harvard-educated professor of Latin at Cornell

University (from 1880-1892) and afterwards (until retirement in 1920) at the newly

founded University of Chicago, where he also served as head of the Latin

department, and Harriet Swinburne Hale (1853-1928), a graduate of Vassar

College. Swinburne’s siblings included Virginia Swinburne Hale (1887-1981), Margaret Hale

(1891-1962) and Gardner Hale (1894-1931). Virginia and Gardner became artists,

and Gardner

Swinburne

was educated at Philips Exeter Academy ,

and Harvard University New York , he lived in Greenwich

Village , where he made many friends among writers, while he also

became prominent in various liberal groups. In 1921, his partner Walter Nellis

at the New York

In 1910 he

married Beatrice Forbes-Robertson, an actress and niece of Sir Johnstone

Forbes-Robertson. They had three daughters. During World War I he served in France

Swinburne

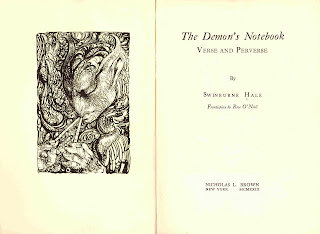

Hale published his only book in the summer of 1923: The Demon’s Notebook—Verse and Perverse (New York Philadelphia

before moving to New York

The Demon’s Notebook was reviewed

favorably by Henry Longan Stuart in The

New York Times. Stuart wrote: “At his

best and most serious, Mr. Hale is astonishingly good” (July 8, 1923). What Stuart doesn’t say is that for much of

the volume, Hale is not very serious at all.

The result is an unsatisfying book, which will be remembered by

posterity more for the frontispiece than for any of the poems inside. To give a few examples, the first poem in the

book, “The Demon”, begins: “Let the

Demon work in you! / Do not cast him out! / He knows better than you do / What

he is about!”. In the final poem in the

“Verse” section, “Dedication” (To Rose O’Neill), Hale writes:

But you, the Master-Mistress of my mind,

Whose Demon sits high-throned above my stars—

But you, whose passionate pinions know no kind,

Whose scars are burnt with scars—

You will divine my song in your far place,

And call it with your wings, and hold it high;

And underneath the dark of that embrace

Young songs shall cry.

In the “Perverse” section, Hale writes in the poem “The God

in the House”:

God is moving round my house

Setting things to rights.

I hear his step upon the stair,

But like a savant in my lair

Crouch and nurse my fine despair. . . .

He wants to make of this my house

A sanitary sight.

He thinks it has a curious smell—

But I should do so very well

If I could keep my funny hell.

Hale spent

the summer of 1924 in Taos ,

New Mexico

Swinburne

Hale soon left Taos Westport ,

Connecticut